Beyond its bright pop of color and tart flavor that many have come to associate with celebrations, this small berry holds deeper cultural significance worth exploring. In the following pages, I hope to shine some light on the cranberry’s varied history, uses, and cultural impact and invite readers to gain a new perspective and appreciation for this American fruit.

Also check out my attempt to implement organic practices on my small farm.

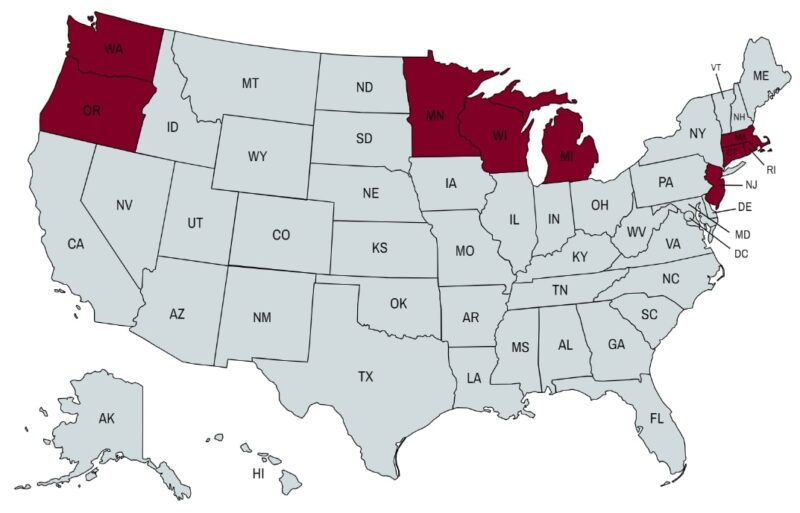

Where does it Grow?

Cranberries are native to certain regions of North America. They seem to thrive best in areas with wet, acidic soil like you often find in bog lands. The cranberry plant is an evergreen shrub that spreads across the ground in a low, vine-like way.

It produces bright red berries each year. Scientists have discovered cranberries do well in places that have sandy or peat-filled soil, and you can notably find large patches of them in states like Massachusetts, Wisconsin, New Jersey, and Oregon.

An interesting thing about cranberries is that their berries aren’t quite like other fruits – they actually float! This is because the berries have air pockets inside. For cranberry farmers, this floating ability makes it easier to harvest the crops from bogs.

Native American Tradition

For centuries, tribes such as the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Algonquin tribes incorporated cranberries into their traditions. In the fall, they would gather the berries as a valuable food source, knowing the fruits would help nourish them through the long winter months.

Cranberries provided both sustenance and natural remedies. The tart berries could enliven meals when other foods grew scarce. Native tribes also combined it with fat and dried meat – a popular food called Pemiccan.

The Cranberry in American Cuisine

Cranberries are quite common in American cuisine, especially as part of Thanksgiving dinners.

Thanksgiving Tradition

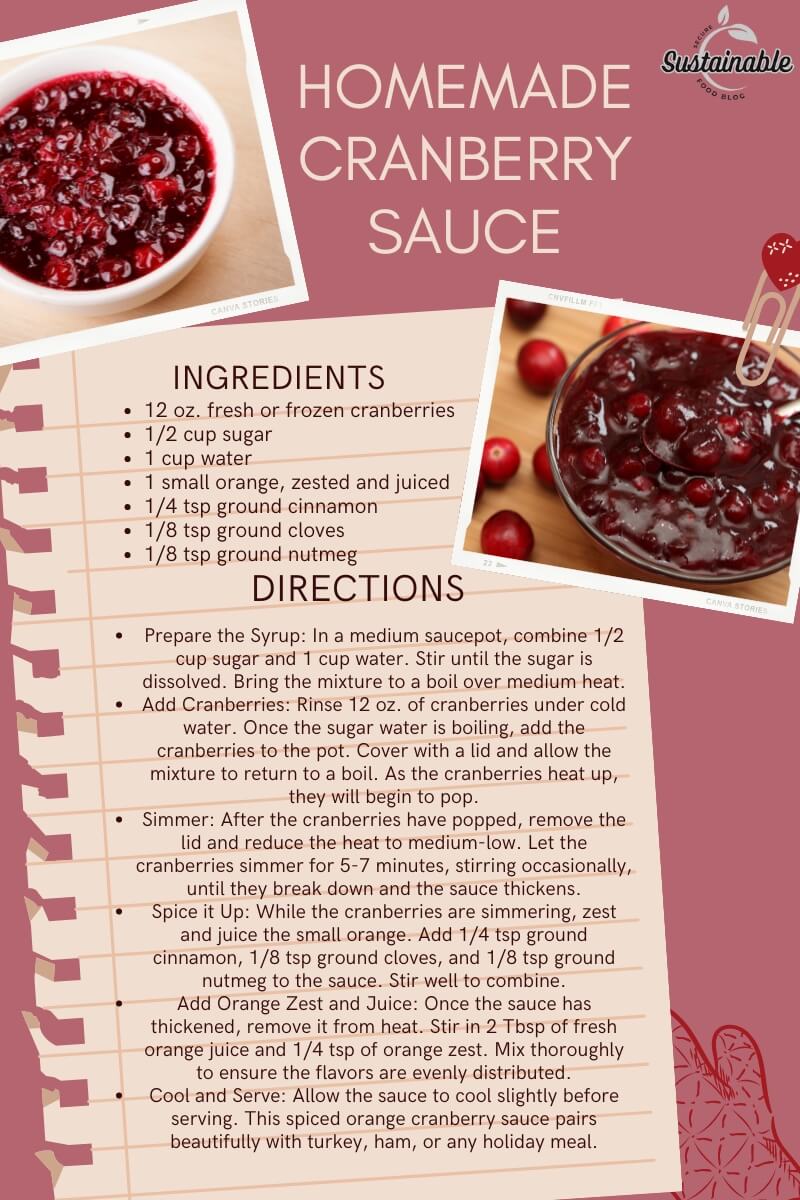

We simply cannot discuss cranberries without mentioning their iconic role in Thanksgiving. The dinner tables across the United States all include cranberry sauce, a sweet and tart condiment made from cooked cranberries, sugar, and various flavorings. It’s perfect with turkey and other dishes, adding a unique flavor and a touch of tradition to the meal.

- Homemade Cranberry Sauce: Many families take pride in making their cranberry sauce from scratch, using recipes that have been passed down through generations.

- Cranberry Relish: Some prefer a chunkier, less sweet cranberry relish that includes ingredients like orange zest, chopped nuts, and a hint of spice.

Use in Everyday Cooking

Here are some creative ways cranberries are used in American cuisine:

- Baking: Cranberries make delicious additions to baked goods, including muffins, scones, and bread.

- Salads: Dried cranberries are often sprinkled on salads, providing flavor, color, and texture.

- Cocktails: Cranberry juice is popular for cocktails. The classic Cranberry Vodka, Cape Codder, and Cosmopolitan are just a few examples.

Health Benefits of Cranberries

Cranberries offer an array of nutritional advantages that can positively impact one’s well-being. Whether enjoyed fresh, dried or as part of juices and products, this American fruit delivers valuable nutrients and compounds.

Rich with Antioxidants

- Cranberries are full of antioxidants like vitamin C and phytonutrients that combat oxidative stress.

- These antioxidants have been linked to reduced risks of chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer.

Cardiovascular Support

Studies show cranberry antioxidants can improve cardiovascular health by lowering blood pressure and disease risk.

Cancer Prevention Potential

Certain phytonutrients in cranberries may inhibit cancer cell growth, especially for breast and colon cancers. More research is ongoing.

Urinary Tract Health

This fruit also contains proanthocyanidins that prevent harmful bacteria from adhering to the urinary tract lining. This helps prevent urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially for susceptible individuals when consuming cranberry juice or supplements.

Proanthocyanidins may also work in the stomach to reduce the risks of ulcers and other gastrointestinal issues.

FAQ

1. Are cranberries only grown in the United States?

No, while cranberries are native to North America, they are also cultivated in Canada, Chile, and other regions with suitable climates.

2. Can I freeze fresh cranberries?

Yes, fresh cranberries can be frozen for extended storage. Simply rinse, dry, and place them in a freezer-safe bag or container.

3. Are cranberries related to blueberries?

Cranberries and blueberries are both members of the Vaccinium genus, but they are distinct species with different flavor profiles.

4. Can cranberries be grown in home gardens?

Yes, cranberry plants can be grown in home gardens, provided you have the right soil conditions and space for them to spread.

Final Words

As you can see, this fruit is more than just a tasty snack as we can use it for much more, such as as a spice in meals. Also, what makes it even more important is the health benefits it provides.